**This essay contains spoilers for Tiger and Bunny as well as the movie Tiger and Bunny: The Rising**

As much as Tiger and Bunny is a story about superheroes, it’s also a drama about human relationships. To that end, director Keiichi Satou, character designer Masakazu Katsura, and scriptwriter Masafumi Nishida have carefully crafted a unique set of believable characters, each with their own gestures, speech patterns, and rich inner worlds. One of my favorite things about Tiger and Bunny is the variety of gender portrayals of its characters. Too many shows with ensemble casts fall into the trap of putting together a team of stereotypes: the Aggressive Young Protagonist, the Strong Silent Mentor, the Deadpan Snarker, and The Girl. While the male characters are distinguished from each other by their personalities, The Girl’s only defining character trait is her gender (and all of the stereotypical trappings that go along with that – oversized breasts, emotional vulnerability, nurturing kindness…). Tiger and Bunny goes above and beyond this trap, portraying male and female characters that are humans first and heroes second. Nishida’s writing demonstrates an awareness of the complexity of masculinity and femininity that is rarely seen in anime.

I could spend a long time talking about the masculinities portrayed in Tiger and Bunny – the generation gap between Kotetsu and Barnaby, or Antonio’s leather pants and hairy chest versus Ivan’s slouch and sukajan (all of which are portrayed as equally valuable ways of being a man and a hero), but it’s easy enough to find a variety of contrasting male characters in one anime. What makes Tiger and Bunny special is its diverse portrayal of femininities, particularly Karina, Pao Lin, and Nathan.

In her revealing Blue Rose costume, Karina is the most overtly sexualized of all of Tiger and Bunny’s female characters. The camera doesn’t hesitate to pan across her posterior when she rides into the crime scene on her motorcycle. However, what makes Karina stand out compared to other scantily-clad anime heroines is that she is aware of her sexualization and actively responds to it. Karina joins the cast of Hero TV to achieve her dream of becoming an idol singer, and the Blue Rose costume and personality are set by her company to help her achieve popularity. The viewer is encouraged to see the contrast between Blue Rose, a sexually confident, domineering character, and Karina herself.When the camera is tracing Blue Rose’s body, we are seeing her through the lens of Hero TV, complete with over-the-top color commentary, and not taking advantage of her by peeping on a private moment. Karina doesn’t passively accept this state of affairs, either. She complains to her company about her character’s catchphrase, and spends the beginning of the series reminding everyone around her that being a hero is not her end game. The way she is sexualized at such a young age is also problematized when her father voices concerns about her costume. Blue Rose occupies a complex position in the story of simultaneously providing fanservice while providing a commentary on the sexualization of female characters in animation and advertising.

The development of Karina’s feelings towards Kotetsu is another interesting aspect of her character. When a girl develops a crush on another character, it is often used to either create drama and tension between the cast, or to spur a romantic plotline. Karina’s crush on Kotetsu does neither. Instead, it is used as an opportunity to show Karina’s emotional vulnerability, and as a way to bring the cast closer together. Although Karina’s feelings are sometimes used for humor, such as when everyone in the room can tell why she’s acting strange except for Kotetsu, her feelings are never laughed at. Although Kotetsu is very unlikely to reciprocate or even recognize her affections, Karina’s crush is not shown as a waste of time. It’s a conversation topic with her high school friends that depicts Karina’s youthful naïveté, and it ultimately establishes a strong link between herself and Kotetsu. After all, when Maverick erases the heroes’ memories and convinces them that Kotetsu is a villain, Karina is the first to doubt the false memories and remember the real Kotetsu.

The other young female hero in the cast is Pao Lin. Compared to Karina, Pao Lin is a definite tomboy. She refers to herself as “boku,” a Japanese first person pronoun usually used by boys, and she dislikes dresses and girly accessories. Her brightly-colored costume conveys an image of youthful energy rather than overt femininity, and her hero name, Dragon Kid, avoids gender categorization as well.

However, Episode 9, “Spare the Rod and Spoil the Child,” explores Pao Lin’s feminine side. The episode starts with Pao Lin’s caretaker Natasha trying to convince her to wear a flower hairclip sent as a gift from her parents and asking her when she will grow out of calling herself “boku.” When the heroes are assigned to watch the mayor’s baby, Pao Lin proves that she has better nurturing skills then Kotetsu, despite Kotetsu having a daughter himself. Pao Lin takes over the primary babysitting role, but then she and the baby get kidnapped by a trio of NEXT sisters. After the kidnappers are defeated and the baby is returned safely to his mother’s arms, Pao Lin is reminded of the importance of her bond with her own parents, and decides to wear the flower hairclip.

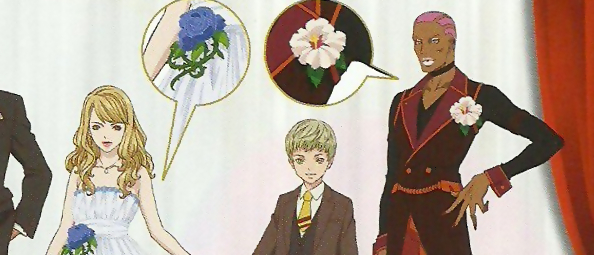

There are a couple of different ways to interpret this episode. Natasha’s comments imply that Pao Lin’s tomboy qualities are something she will one day grow out of. Because Pao Lin assumes the mature, traditionally feminine role of caring for a child and then subsequently accepts the feminine accessory she had rejected at the beginning of the episode, it’s possible to read this episode as Pao Lin beginning to grow up and move towards a more feminine self-image. However, considering the rest of the series, and especially the movie The Rising, I don’t think this is the case. The Rising takes place after the end of the TV series, featuring new character designs for the entire cast. Pao Lin undergoes the greatest change in the time between the TV series and the film, and her character design actually becomes less feminine. Her hair gets much shorter, and she trades her tracksuit for a tank top and cargo shorts. For Hero TV’s formal occasions, she now wears a suit, complete with vest and tie, instead of her lace-trimmed dress and Mary Janes. As Pao Lin gains more agency over her public image, instead of growing up into a conventionally feminine young woman, she seems to be continuing to explore the masculine aspects of her personal style and expression. When The Rising is considered alongside the main series, it becomes clear that Tiger and Bunny does not require or expect Pao Lin to grow out of her tomboyish traits. Instead, her masculine fashion and speech are something that makes her who she is, and episode 9 shows that these traits can coexist with more stereotypically feminine activities such as caring for children. That Pao Lin can feel as comfortable with babysitting as she is with kung fu shows that she is truly a uniquely capable hero.

The final hero I want to explore is Nathan, AKA Fire Emblem. Nathan plays with gender in an even more overt way than Pao Lin. He wears full makeup at all times, and when he’s out of his hero costume, he wears as much pink and sequins as he can. He speaks using onee kotoba (オネエ言葉), a form of exaggerated feminine Japanese used by gay men, but he will sometimes play with the pitch and tone of his voice, speaking in a more masculine way when he wants to sound angry or threatening. As Fire Emblem, his bodysuit leaves little of his masculine physique to the imagination, complete with fiery yellow highlights that emphasize the shape of his crotch, and he completes the outfit with high heels. Nathan is unabashedly masculine at the same time as he is unabashedly feminine.

Nathan’s character exists in the context of Japanese stereotype known as okama: a pejorative term for a crossdressing man who is attracted to other men. Although okama performers are not unknown in Japanese television, they are usually associated with comedy or the sex industry. In anime, okama characters are rarely portrayed sympathetically. They are usually bit roles who exist for humor, laughed at for their gender presentation or for their sexual advances towards other male characters. Tiger and Bunny is notable for portraying a gender-nonconforming, homosexual character but refusing to let him become a joke.

Nathan is readily accepted by all of Tiger and Bunny‘s heroes, and his gender presentation and sexual orientation are never remarked upon. Pao Lin and Karina clearly consider him “one of the girls” – he is often shown going out for meals and relationship talk with the two of them. He has a similarly comfortable relationship with the male heroes – Kotetsu banters back when Nathan jokingly flirts with him, and although Antonio understandably objects when Nathan’s hands wander, he never avoids being around Nathan. In fact, Nathan often acts as the glue that holds this diverse and often conflicting group of heroes together. He is the most mature adult among them, offering advice and perspective or breaking up arguments when needed.

The Rising explores the depths of Nathan’s emotions and his inner struggle to become the confident and unapologetic person that he is. When a NEXT traps Nathan in a nightmare based on his past memories, we see that he can be the one who nurtures the other heroes and holds their team together because he knows what it’s like to hurt alone. We also see the great lengths the other heroes will go to protect and defend him, staying by his side as he fights his internal battle.

In Hero TV Fan Book – The Rising, Nishida writes that he was inspired by stories of real gay and lesbian people he talked to: “As part of my job [as a writer], I listen to stories from many different kinds of people, but when I talk with gay men or lesbians, they often say that, even years after coming out, no matter how happy they are, there is still a feeling lurking somewhere deep in their heart that says ‘Is it really okay for me to be this way?’ Even at the point where the person thinks they’ve overcome their doubts, a faint fragment of that feeling remains. Those are the stories that I heard. In this film, by having Johnny pry into and amplify that feeling, I wanted to create a scene where, whether he wants to or not, Nathan has to face his doubts (page 43, my translation).”

And face them he does, with dignity and compassion, like Nathan does all things. After hearing Pao Lin’s impassioned words in his defense, he snaps out of Johnny’s spell. He embraces the raw, hurting, scared, and angry part of himself, declaring that he’s happy to have been born himself, and literally leaping out of his nightmare. In his final battle with Johnny, Nathan even reclaims the very slur used against him in his past, declaring “They say that a man is made of bravery and a woman is made of love. Then what does that mean for okama? We’re invincible!”

A sympathetic portrayal of an LGBT character that doesn’t end in tragedy is very rare in Japan, so having a self-proclaimed okama hero triumphantly declare that his experience of gender makes him invincible is a rare and precious moment in television. Using this moment not in a DVD extra or an OVA that would only be seen by die-hard fans, but in a film release that screened not just in Japan but internationally? That’s even more special.

The main series of Tiger and Bunny portrays Nathan as a superhero, starring on a major television program, owning his own company, and being completely himself. And the movie The Rising portrays the hurdles he had to overcome to get there, and the unrelenting support he has earned from his friends, simply by being true to himself. In its portrayal of Nathan, as well as Pao Lin, Karina, and the rest of the Hero TV cast, Tiger and Bunny shows that heroes come in all shapes, sizes, and gender presentations, and all types of hero are worth celebrating.